Blog Archive

Followers

Come Reason's Apologetics Notes blog will highlight various news stories or current events and seek to explore them from a thoughtful Christian perspective. Less formal and shorter than the www.comereason.org Web site articles, we hope to give readers points to reflect on concerning topics of the day.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

Archaeology and the Bible (podcast)

The Bible is unique among sacred texts in that it is set against a historical backdrop. Do recent archaeological discoveries validate or discredit the Biblical accounts? Listen to this complete series as Lenny explores the relationship between the Bible and archaeology and shows why the Bible can be considered reliable historically.

Thursday, May 28, 2015

"Lost Gospels" are to the Gospels as Sci-Fi is to Shakespeare

Yesterday, I began to discuss the so-called Lost Gospels, those second and third century writings claiming to be Gospel accounts by Apostles like Peter, Thomas, and Judas. As I noted, the Apostles names applied to these writing are clearly forged. The writings themselves are too late to come from those living at the same time Jesus ministered, unlike the four recognized Gospels of the New Testament. However, that doesn't stop some skeptics from trying to promote the idea that these documents are somehow on par with the canonical Gospels.

In his book Lost Christianities, Bart Ehrman makes the claim that there was some kind of competition between the four Gospels we know and these other writings. He states:

The Gospels that came to be included in the New Testament were all written anonymously; only at a later time were they called by the names of their reputed authors, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. But at about the time these names were being associated with the Gospels, other Gospel books were becoming available, sacred texts that were read and revered by different Christian groups throughout the world: a Gospel, for example, claiming to be written by Jesus' closest disciple, Simon Peter; another by his apostle Philip; a Gospel allegedly written by Jesus' female disciple, Mary Magdalene; another by his own twin brother, Didymus Judas Thomas.1Ehrman then claims "Someone decided that four of these early Gospels, and no others, should be accepted as part of the canon," and then asks "How can we be sure they were right?"2

Obfuscating the Late Composition of the Gnostic Texts

As a New Testament scholar, Ehrman is being extremely disingenuous here. First, notice the phrasing of the sentence "about the time these names were being associated with the Gospels, other Gospel books were becoming available." It is written tom mislead readers that the Gnostic accounts are nearly contemporaneous with the Gospels. That isn't true. The Gospels were well known and circulated from the first century onward. As I've shown here and here, early church fathers named the authors of all four of the Gospels by 100 AD and no other candidates were ever seriously advanced. The Gnostic texts weren't even written until the second and third centuries, and that's when the church began making lists of what counts as Scripture and what doesn't. Thus, when Ehrman claims that "other Gospel books were becoming available," he means other Gospel books were being written. And when he claims this happened "about the same time these names were being associated with the Gospels" he means the Church put down on paper a list of Gospels bearing the names Matthew. Mark, Luke, and John.But what of Ehrman's other claim that these texts were considered sacred, revered and worthy to be considered as part of the Christian Scripture? Internet skeptics make similar assertions all the time. However, these Gnostic texts, although labeled by their forgers as "Gospels" don't hold a candle to the real Gospels. In fact, all it takes is a quick read of them to show they are about as similar to the Gospels as a pulp science fiction novel is to one of Shakespeare's plays. Let's take a look at a few snippets to get a flavor.

Gospel of Peter

Ehrman points to the Gospel of Peter as a potential candidate for Scripture. Yet, in the Gospel of Peter, Pontius Pilate becomes free of all guilt because he washed his hands, thus flipping John's account on its head. It was the unwashed Jews and Herod that are supposed to take the blame for Jesus's death:But of the Jews no man washed his hands, neither did Herod nor any one of his judges: and whereas they would not wash, Pilate rose up. And then Herod the king commanded that the Lord should be taken into their hands, saying unto them: All that I commanded you to do unto him, do ye.3

Such a re-envisioning of Herod's washing as a good thing is remarkable enough, but what's worse is how the account of the resurrection portrays Jesus coming out of the tomb on Sunday morning accompanied by two angels. All three of them have elongated necks and there a floating cross that answers God the Father! The passage reads:

They saw again three men come out of the sepulchre, and two of them sustaining the other and a cross following, after them. And of the two they saw that their heads reached unto heaven, but of him that was led by them that it overpassed the heavens. And they heard a voice out of the heavens saying: Hast thou (or Thou hast) preached unto them that sleep? And an answer was heard from the cross, saying: Yea.4

Certainly, the Gospel of Peter does not hold the same historical weight as the Gospel accounts.

Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas was another account that Ehrman mentions. This text is interesting because it is probably the earliest of the Gnostic texts written sometime in the early or middle second century. But to call it a Gospel is to malign the term. First of all, it isn't a narrative of Jesus' ministry. It is only 114 verses long and is a collection of supposed sayings or teachings of Jesus. About a third of these are copied from the existing Gospel accounts. About a third are teachings not necessarily incompatible with Christian doctrine, but we don't know if Jesus said them. The last third, though, are completely Gnostic.For example, take verse 22, which is comprised of double-speak :

When you make the two into one, and when you make the inner like the outer and the outer like the inner, and the upper like the lower, and when you make male and female into a single one, so that the male will not be male nor the female be female, when you make eyes in place of an eye, a hand in place of a hand, a foot in place of a foot, an image in place of an image, then you will enter [the kingdom].5Or verse 30, which is not only confusing but seems to reject monotheism:

Where there are three deities, they are divine. Where there are two or one, I am with that one.6Finally, Thomas ends with a disturbing bit of Gnostic ideology where Jesus states only men can get into heaven and Mary Magdalene must be turned into a man to enter the Kingdom:

Simon Peter said to him, "Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of life." Jesus said, "I myself shall lead her in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven.7I could go on, but I think my point is made. The so-called Lost Gospels are nothing of the kind. They weren't lost, they were rejected. And they weren't Gospels, because they are devoid of the Good News of salvation. Of course, people can spiritualize anything; that's why a significant number of people in England and Wales identified themselves as holding to the Jedi faith.8 Holding that the Gnostic texts were serious candidates as Gospels falls into the same category as believing Obi-Wan Kenobi is a religious scholar. It makes me wonder in what way Dr. Ehrman watches Star Wars.

References

2. Ehrman, 2003. 4.

3. Gospel of Peter, I.1-2. Translated by M. R. James. The Gnostic Society Library. The Gnostic Society Library, 1995. Web. 28 May 2015. http://www.gnosis.org/library/gospete.htm.

4. Gospel of Peter,XI.38-42.

5. Gospel of Thomas. 20. Translated by Stephen Patterson and Marvin Meyer. The Gnostic Society Library. The Gnostic Society Library, 1994. Web. 28 May 2015 http://gnosis.org/naghamm/gosthom.html

6. Gospel of Thomas, 30.

7. Gospel of Thomas, 114.

8. "'Jedi' Religion Most Popular Alternative Faith." The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 11 Dec. 2012. Web. 28 May 2015. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/religion/9737886/Jedi-religion-most-popular-alternative-faith.html.

Thursday, May 07, 2015

Why Those "Lost Books" of the Bible Don't Cut It

The answer is yes, there is. I've begun t look at three specific attributes that all biblical texts share that are not true of any so-called "lost books" of the Bible. Yesterday, I discussed how all of the biblical books shared a specific authority, both in their claim to speak on God's behalf and in their recognition as authoritative voices given their proximity to the apostles. Today, I'd like to look at the second common attribute of scripture: its acceptance throughout the early Christian Church.

Christianity has always been a faith that claims a certain kind of unity. When the disciples tried to stop a man who wasn't part of their group from casting out a demon using his name, Jesus rebuked them, saying "He who is not against you is for you" (Luke 9:50). The Christian church is one church, one body of Christ with many members (1 Cor. 12:12-13). The early church held this concept of unity highly, even incorporating it into their statement of faith, the Nicene Creed, which states "We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church." Protestants today may be thrown by the world "catholic;" it doesn't refer to the Roman Catholic Church (Capital "C"), but it simply means "universal."

The Universal Acceptance of the Biblical Books

Because Christianity is both apostolic and catholic, it shouldn't surprise many that the writings we recognize as scripture are also apostolic and catholic. The Hebrew Old Testament was seen as authoritative and called scripture by both Jesus and the apostles. The early church fathers would also cite OT books as authoritative. When a man born just one generation after the Apostles named Marcion sought to throw out the Old Testament, he was condemned as a heretic. The Old Testament was accepted and understood as being the word of God and proclaiming the coming of Jesus as Messiah.The twenty-seven books of the New Testament were also universal in their acceptance, but not quite as neatly. While the Old Testament had been established as a single corpus, the New Testament was still being formed as the Church was being formed. Also, because early Christianity was spread across parts of Africa, Asia, and Europe, distributing the apostles' writings became more challenging. Still, most of the texts were accepted by a wide majority of the church very, very quickly, normally within the 20 to 40 years of their actual writing.

The sharing of authoritative texts began very early within the church. Paul sets this model in his letter to the Colossians, where he writes, "And when this letter has been read among you, have it also read in the church of the Laodiceans; and see that you also read the letter from Laodicea" (Col, 4:16). It is because letters were shared and copies were made so other churches could refer back to them that we have as many New Testament manuscripts as we do. While Paul's letters might be addressed to a certain church or person, other apostles would write to the church as a whole. Peter begins his first epistle addressing it to "those who are elect exiles of the Dispersion" (1 Pet. 1:1). James uses the same language. Jude addressed his to "those who are called, beloved in God the Father and kept for Jesus Christ" while John writings make the distinction between those in the faith ("us") and those not of the faith ("them) in 1 John 2:19. Clearly, he was offering instruction to the church as a whole.

Disputed Books of the New Testament

Because of the time it could take for books to be copied and passed along to other areas of the world, not every church had recognized every book immediately. Others would be wary of books that they saw as suspect, such as 2 Peter or Jude. Eusebius named five books as being controversial (James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Jude.) Yet these books were quoted by various church fathers prior to this and some were included in lists of scripture such as the Muratorian Canon.1 By 367, Athanasius lists all the books of the New Testament as authoritative and it reflects the exact twenty-seven books we have today.The contrast between the accepted New Testament books and those claiming to be "lost books" is staggering. Various church fathers like Origen, Irenaeus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Clement of Alexandria and others would write of them and condemn them. No gospel other than Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were ever supported by anyone for inclusion in the canon.2 A couple of epistles were, such as the Shepherd of Hermas or the Epistle of Barnabas. These were ultimately rejected as not being connected to the apostles and not being universally recognized within the church as scripture.

References

2. Geisler and Nix, 301-316

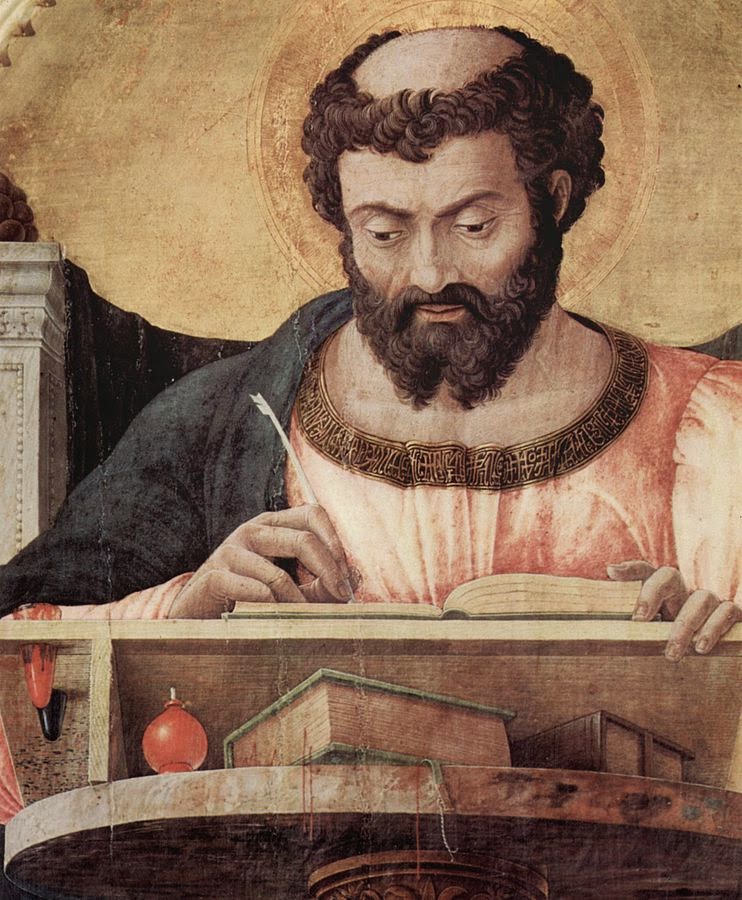

Image courtesy Malcolm Lidbury [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Tuesday, May 05, 2015

Does the Story of the Resurrection Have a Flaw?

The resurrection of Jesus from the dead is one of the most well-attested events in antiquity. We have testimony from multiple independent sources that detail the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Jesus and we see the impact of his resurrection through the transforming nature of Christianity. I've previously offered several lines of evidence for why the resurrection is a historical reality. However, on an article discussing the evidence of the empty tomb, one commenter claimed that the story of the resurrection has a huge hole in it. He writes:

I had never heard of this until today: How many Christians are aware that Jesus' grave was unguarded AND unsecured the entire first night after his crucifixion??? Isn't that a huge hole in the Christian explanation for the empty tomb?? Notice in this quote from Matthew chapter 27 below that the Pharisees do not ask Pilate for guards to guard the tomb until the next day after Jesus' crucifixion, and, even though Joseph of Arimethea had rolled a great stone in front of the tomb's door, he had not SEALED it shut!The empty tomb "evidence" for the supernatural reanimation/resurrection of Jesus by Yahweh has a HUGE hole in it!

Anyone could have stolen the body during those 12 hours!

He then quotes Matthew 27:57-65, where we find the following relevant portion:

The next day, that is, after the day of Preparation, the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered before Pilate and said, "Sir, we remember what that impostor said while he was still alive, ‘After three days I will rise again.' Therefore command the tomb to be made secure until the third day; otherwise his disciples may go and steal him away, and tell the people, ‘He has been raised from the dead,' and the last deception would be worse than the first." Pilate said to them, "You have a guard of soldiers; go, make it as secure as you can." So they went with the guard and made the tomb secure by sealing the stone."Matthew thus lays out the timeline that Jesus died on the Day of Preparation (that is, the day before the Sabbath). We would understand this as Good Friday. Then, the Jewish leadership went to Pilate and asked that Jesus's tomb be guarded given the claim that he would rise again. Pilate acquiesces, and a guard is dispatched. The commenter then asks:

So when did the guards show up to the tomb? Early the next morning or late in the afternoon? If late in the afternoon, the tomb of Jesus had been unguarded and unsealed for almost TWENTY FOUR hours!The empty tomb is NOT good evidence for the resurrection claim. The most plausible explanation, based on the Bible itself, is that someone stole or moved the body!

Reading Historical Texts Carefully

Objections like these are interesting because on the surface they sound plausible. However, many times we bring our own assumptions into such a reading without realizing it. I think this is what has happened here.First, it's important to realize that the source of this exchange is Matthew's Gospel. Matthew is the most Jewish of the four gospel accounts and his account of the time of Jesus's crucifixion (Matt. 27:45) reflect the Jewish rather than Roman accounting of time. It is well known that for Jews a new day begins at sundown. This means the term "the next day" doesn't imply a minimum of twelve to twenty-four hours later. In fact, we know that Jesus was buried very close to sundown because the women didn't have enough time to properly prepare his body, which is why they were going back to the tomb on Sunday morning. It's also why Pilate had the legs of the others condemned broken; it would speed their death so they could also be dealt with before the onset of the Sabbath.

Secondly, we know that the Jewish leadership was familiar with Jesus's claim to resurrect in three days, and were so deeply concerned about some manipulation to that end that they approached Pilate on the Sabbath to ask for a guard. Pilate allows them to use their own temple guards to secure the tomb.1 But this would happen rather quickly. The crucifixion is a public event and we know the priests were watching Jesus die. Since Jesus's prediction of resurrection came well before his crucifixion, it must've been on their minds. Why would they have waited until the next morning or afternoon? Haste is necessary to effectively stop any tomb raiding by disciples.

Wouldn't the Guards Have Checked?

Thirdly, we have to think about the charge given to the guard. Are they to simply guard the tomb from that point forward no matter in what condition it currently is found? The guards are dispatched with this very crucial task that is of such concern that it unites the chief priests and the Pharisees in a common goal. They get to the tomb and they must see it in one of two conditions. Either the stone has been sealed over the tomb or the tomb is open. If the stone has been placed over the tomb, then they guard that configuration. But, we read later that the women (who were concerned about moving the stone) found it rolled away on Sunday morning. Who did that? Why would the guard even allow that to happen?The second choice is the stone wasn't sealed but the guards sealed it there. Two questions now surface, did the guards bother to look inside the open tomb to make sure that the body was still in there? If the challenge is to keep people for stealing the body, don't you check to make sure the body is still there? If you don't and seal the tomb anyway, the question still remains why did the guards allow someone else to come up and open the tomb at all? Isn't your assignment to not let that happen?

No matter what amount of time transpired between Jesus's death and the guards arriving at the tomb, the question of who moved the stone becomes the undoing of the "disciples stole the body" claim. As Craig Keener notes, "Those who have ever had their beliefs or deep hopes shattered will recognize that Jesus' death should have disillusioned the disciples too much for them to fake a resurrection (which would also be inconsistent if they expected one.) Though the corpse remaining in the tomb would have easily publicly refuted the resurrection claim, had the authorities been able to produce it, an empty tomb in itself would not be self-explanatory."2 IN other words, only in the context of the resurrection does the empty tomb have evidentiary power. Yet, the fact that the tomb was empty is proven by the story, as N.T. Wright notes "The point is that this sort of story could only have any point at all in a community where the empty tomb was an absolute and unquestionable datum." 3

Lastly, the stolen body cannot explain the conversion of Saul of Tarsus, who believed the chief priests and sought to exterminate what he considered a blasphemous threat to his beliefs.

So the "hole" in the resurrection story turns out to be evidence for the resurrection itself. Without an open tomb, one cannot claim an empty tomb. But since the tomb as found empty, which is common knowledge as N.T. Wright notes, then it lends credence to the resurrection account.

References

2. Keener, Craig S. The Historical Jesus of the Gospels. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub., 2009. Print.342.

3. Wright, N. T. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2003. Print. 638.

Saturday, April 25, 2015

Scholars Agree: Luke and Acts are History

In his monumental commentary on the book of Acts, Dr. Craig Keener looked at proposals for the book of Acts to be considered within the genre of novel (as a fictional story), of epic (like Homer's Iliad), as a travel narrative, and as a pure biography. Keener then explains that the best understanding of Acts is as a book narrating history. He is not alone in this conclusion, as he writes:

The dominant view today, earlier argued by such Lukan scholars as Martin Dibelius and Henry Cadbury, is that Acts is a work of ancient historiography. As Johnson notes in the Anchor Bible Dictionary, "The reasons for regarding Luke-Acts as a History are obvious and, to most scholars, compelling: One sampling of recent proposals concerning Acts genre is instructive: two proponents for Acts as a novel, two for epic, four for biography, and ten for various kinds of history. More examples could be listed in each category, but the sampling is nevertheless helpful for getting a sense of proportion: even in a list emphasizing the diversity of proposals, history appears five times as often as the novel and, together with biography, seven times as often as the novel. A similar sampling finds history the most common proposal, with eight examples, and biography the second most common, with two examples, and lists five examples of all other genre proposals put together. Many scholars most conversant in ancient historiography would also concur with Hengel and Schwemer that those who deny Acts as acceptable first-century historiography need to read more ancient historiography "and less hypercritical and scholastic secondary literature."1In the footnote to that last quote, he explains that Hengel and Schwemer complain "most NT scholars cannot handle the primary sources well enough to discern accurate from inaccurate scholarship and that 'it is easier to keep hawking around scholastic clichés and old prejudices pseudo-critically and without closer examination, than to occupy oneself with the varied ancient sources which are often difficult to interpret and remote.'"

The Jesus-myth crowd is actually in worse shape than those that Hengel and Schwemer complain against, since they are hawking around populist, not scholastic, clichés fueled only by their bias and not by the examination of the evidence.

References

Keener, Craig S. Acts: An Exegetical Commentary. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012. Print.81-82, footnote 10.Wednesday, April 01, 2015

The Gospel of Judas Rears Its Head on CNN

These comments are from the CNN special series Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery which has been airing on Sunday nights. The March 25, 2015 episode was entitled "The Gospel of Judas" and highlights the text that received so much attention when the National Geographic Society published a translation of the rare manuscript in 2006. National Geographic promoted its translation in a special, saying it was "a lost gospel that could challenge what is believed about the story of Judas and his betrayal of Jesus."2 Back then there was much fanfare, but little to surprise or sway biblical scholars. But the media always love to provoke, especially if they can undermine the traditional biblical accounts with any wild speculation they can find. So, nine years later, CNN offers an entire episode on the Gospel.

In fact, the Gospel of Judas wasn't groundbreaking even in 2006. Scholars had known for some time that a document called the Gospel of Judas existed from the writings of the early church fathers, particularly Irenaeus. What's amazing to me is how some otherwise intelligent people lose all sense of bearing when they are confronted with an ancient text that has the word "gospel" on it. Just because a document has the word "gospel" at the top, doesn't mean it even comes close to being on par with the canonical gospels.

Still, the discovery of an actual copy of the text is significant. Was the Gospel of Judas hidden as the result of some kind of conspiracy to keep power in the hands of a few? Does it place the canonical gospel stories of Matthew, Mark, Luke , and John in doubt? Hardly. Let's examine just what this document is and then we'll look at why it really tells us nothing about the formation of early Christianity.

Another Gnostic Gospel

The Gospel of Judas translation that was recently published comes from a third century manuscript, written in Coptic, an ancient Egyptian language. It contains many strange teachings such as:- Creation was corrupted by lesser gods who made the material world

- Jesus wished to be set free from His material body so He could access the holy realm

- The Gospel holds a type of secret knowledge that only one person (Judas) has

- The rest of the disciples are clueless to the true mission of Jesus

Judas Gospel is Too New to be Bible

Now, I don't want to go into a technical discussion of Gnosticism to show why the Gospel of Judas doesn't hold a candle when compared to the four canonical gospels. We don't need to go that far to show why it should be rejected. We know that the manuscript we have is authentic - which means that it really did come from the third or fourth century. However, that doesn't mean that its contents are true. There's a big difference there. And why am I so sure that the contents of the Judas gospel are false? Well, it's simple. The gospel is too new to be written by the Judas of the Bible. You see, most scholars agree that Jesus' death happened somewhere around AD 33. The gospel is around 100 to 120 years later. Just how old would Judas have to be to write this account? 150? It doesn't make sense. Judas died well before this text originated.The Associated Press interviewed James M. Robinson from Claremont Graduate University and who they said is "America's leading expert on such ancient religious texts from Egypt."3 There, Robinson agrees with this assessment. Robinson states, "There are a lot of second, third, and fourth-century gospels attributed to various apostles. We don't really assume they give us any first century information."4 He concludes that nothing new can be learned about Judas of the Bible from the text.

Secondly, since Judas didn't really have anything to do with this "gospel", we also know that the documents facts are in serious question. Remember, Judas dies during Jesus' crucifixion, so he couldn't have told anyone this special revelation. Therefore, these conversations must be fictional. You see, real gospels have what is known as an apostolic tradition. In other words, the four gospels can be traced back to the apostles themselves. Christians such as Irenaeus understood this and rejected it as a forgery.

Looking at a Modern Example

I think for a good starting point when discussing this text with others, let's look to a more modern example: the forged memos that surfaced during the 2004 presidential election. During the campaign, 60 Minutes reported on the discovery of an Air National Guard memo that suggested favorable treatment for the president. If these documents were accepted as real they could do much damage to his campaign. However, when the memos were scrutinized it became apparent that they were forgeries. Type styles used in the memos were too recent for the documents to have originated in the 1960's when they were purportedly written.I think that no matter which candidate you supported, most news agencies showed maturity in their rejection of the documents as unsubstantiated. Even if one holds that special treatment was afforded Mr. Bush during his National Guard service, these specific memos do nothing to give us new or better information about those charges, simply because they are false testimony. Similarly, a forged gospel of Judas doesn't help us to really understand Jesus, Judas or first century Christianity.

Ultimately, the biggest piece missing from the Gospel of Judas is the gospel message itself. Remember that the word "gospel" means good news. It was called such because early Christians saw their redemption from sin as the good news to share with others. But redemption is the one thing the so-called Gospel of Judas doesn't have. Without that, there's no freedom from sin and no reason to follow Jesus who becomes just another dead man claiming to speak from God.

References

2. "The Lost Gospel of Judas." National Geographic Channel. National Geographic Society. Web. 20 April 2006. http://www9.nationalgeographic.com/channel/gospelofjudas/. Archived page at https://web.archive.org/web/20070623220135/http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/gospelofjudas/

3.Ostling, Richard. ""Expert Doubts 'Gospel of Judas' Revelation"" USAToday. USA Today, 2 Mar. 2006. Web. 1 Apr. 2015. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/science/2006-03-02-gospel-of-judas_x.htm.

4. Ostling, 2006.

Monday, March 30, 2015

How Can the New Testament Be Trusted If the Writers Are Biased?

There's No Escaping Bias

The charge of bias is an easy one to make, but because an author is biased doesn't mean we can't have a certain level of assurance that the events he described did indeed happen. We are all biased in our views; there's no way to escape bias on one type or another. Mike Licona notes that it is common practice for those who record history to "select data because of their relevance to the particular historian, and these become evidence for the building the historian's case for a particular hypothesis."3 Licona compares such actions with a detective as a crime scene who "survey all of the data and select specific data which become evidence as they are interpreted within the framework of a hypothesis. Data that are irrelevant to that hypothesis are archived or ignored. Historians work in the same manner."4 There's no escaping bias.Bias Doesn't Mean Unreliable

Even though all ancient historians had a bias, it doesn't mean that their writings are unreliable or useless. Indeed, if we were to reject ancient historical sources because with writers were biased, we would have to reject pretty much all the accounts of history that have been left to us by folks like Josephus, Herodotus, Pliny, Lucian, and every other author from antiquity. The ancient historian Lucian himself complained about the lack of emphasis one person gave to a significant battle in his memoirs. In his The Way to Write History, he levels charges of bias when he complains, "There are some, then, who leave alone, or deal very cursorily with, all that is great and memorable… and loiter over copious laboured descriptions of the veriest trifles… For instance, I have known a man get through the battle of Europus in less than seven whole lines, and then spend twenty mortal hours on a dull and perfectly irrelevant tale about a Moorish trooper." 5Because the gospel accounts of Jesus are seen today by most scholars as a subset of the ancient biography genre (known as bioi)6, each Gospel writers would have selected certain accounts of Jesus's life and actions to pursue a particular point. Richard Burridge, whom Licona quotes, states the Gospels "have at least as much in common with Greco-Roman [bioi], as the [bioi] have with each other."7 Licona states that for biographies in antiquity:

Each biographer usually had an agenda in writing. Accordingly, they attempted to persuade readers to a certain way of political, philosophical, moral, or religious thinking about the subject. Just as with many contemporary historical Jesus scholars, persuasion and factual integrity were not viewed as being mutually exclusive. It was not an either/or but a both.8The question of bias isn't then will any kind of bias will appear in historical narratives, but whether the writers were so biased that they unreasonably or intentionally distort the events they record. Licona sums up the Gospel writers' motives by quoting David Anne, who states: "While the Evangelists clearly had an important theological agenda, the very fact that they chose to adopt the Greco-Roman biographical conventions to tell the story of Jesus indicated that they were centrally concerned to communicate what they thought really happened."9

It doesn't follow that just because the authors of the gospels were Christians that they were going to be liars any more than it follows that the man who spent some twenty hours describing a Moorish trooper was lying to Lucian. One who assumes so shows his or her own bias against the Gospel records.

References

2. Martin,1991. 78.

3. Licona, Michael R. The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2010. Print. 34.

4. Licona, 34.

5. Fowler, H. W., and F. G. Fowler. "The Way to Write History." Works of Lucian, Vol. II. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1905. Web. 30 Mar. 2015. http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/luc/wl2/wl210.htm.

6. Licona, 202.

7. Licona, 203.

8. Licona, 203.

9. Licona, 204.

Thursday, March 05, 2015

Claims of Contradictions May Display Prejudice

The thing about claiming contradictions is that skeptics can easily make such charges while obstinately rejecting any attempts at understanding possible solutions. Skepticism only seems to run in their favor, as they are less skeptical about the claim of contradiction than they are of the reconciliation of the differences. But this isn't anything new.

Dr. Tim McGrew, who runs the Library of Historical Apologetics organization (check out their Facebook page here), came across this quote, originally written by the British theologian Edward Stillingfleet nearly 200 years ago. He deftly sums up the problem with the immediate assumption of contradiction:

How easily things do appear to be contradictions to weak, or unstudied, or prejudiced minds, while after due consideration appear to be no such things. A deep prejudice finds a contradiction in every thing; whereas in truth nothing but ill-will, and impatience of considering, made any thing, it may be, which they quarrel at, appear to be so. If I had been of such a quarrelsome humour, I would have undertaken to have found out more contradictions in your papers than you imagine, and yet you might have been confident you had been guilty of none at all. When I consider the great pains, and learning, and judgment, which hath been shewn by the Christian writers in the explication of the Scriptures; and the raw, indigested objections which some love to make against them; if I were to judge of things barely by the fitness of persons to judge of them, the disproportion between these would appear out of all comparison.1When Stillingfleet wrote these words, he did not have to deal with the New Atheists or the various charges that pass from page to page on the Internet. Yet, he notes that much intellectual exertion has been given to the study of the scriptures even to that point by those who would critically examine all its aspects. 200 years late, even more scholars have turned a critical eye towards the accounts of Jesus life, death and resurrection, and it still stands as strong as it has since its composition.

It's easy to fall into the trap of expecting ancient documents to conform to 21st century practice, but as Stillingfleet states, drawing on such expectation to make the accusation of contradiction reflects a weak and unstudied mind who may hold a deep prejudice. As for specifics in dealing with contradictions, I've written a series of posts, some of which may be found here, here, and here. I've also offered offered some quick tips to keep in mind.

While the charge of contradiction may be easy to lob, such charges may actually say more about the accuser than the documents. Let's not be too shaken when they appear.

References

Image courtesy Woody Thrower and licensed by the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Unlikely Candidates for Gospel Writers

Why do kids forge notes from their parents, but not the next-door neighbor or a sibling? Usually, it is because it would make the note a whole lot less believable. If a neighbor signed the note, the student would be forced to go to much greater lengths to demonstrate he or she was in the neighbor's care or the neighbor had some legal authority over the child. It complicates things and makes people ask questions in a way that the more widely-recognized authority of the mother and father don't.

Why Forge These Guys' Names?

I bring this point up as I wrap down my little series on the authorship of the Gospels. While it is agreed that the original authors of the gospels didn't sign their names to them (something not uncommon when dealing with a popular level biographical account in the ancient world), they have always been attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. In fact, that's a big point. Those who are skeptical will usually claim that no one knows who wrote any of the gospels. They were anonymous and the names they now bear were attached later. Yet, the gospels themselves claim to come from eyewitness testimony (Luke 1:1-3, John 21:24) and ancient biographers sought out eyewitnesses as the best type of evidence. Richard Bauckham, comments that historian Samuel Byrskog stresses that "for Greek and Roman historians, the ideal eyewitness was not the dispassionate observer but one who, as a participant, had been closest to the events and those who direct experience enabled him to understand and interpret the significance of what he had seen. The historians 'preferred the eyewitness who was socially involved or, even better, had actively participated in the events.'"1Given that involved eyewitnesses would be considered more valuable, then one would imagine that these anonymously-written accounts would offer some more significant apostolic names to be associated with them. Two of the four gospels aren't even names of the apostles: Mark and Luke. Isn't this a bit like picking the next door neighbor to write your absence note? It takes more explaining and weakens the case for their authenticity. Of the two gospels that do bear the names of apostles, Matthew is more relatively obscure apostle, not an Andrew or Peter or James. Only John's gospel account bears the name of one of the "inner circle" of apostles, and his is the one that shows up last. If the pattern was to forge the names onto the Gospels, why wait until John to pick a prominent apostle, unless Matthew, Mark , and Luke actually did write their own Gospels?

No Other Choices

Not only do we have some relatively obscure authors chosen for three of the four gospels, we also notice that there has never been any alternatives offered for the sources of the Gospels. Compare that to a truly anonymous book of the New Testament: the book of Hebrews. Early writers like Eusebius and Athanasius attribute the book to the Apostle Paul. Origen seems to have some misgivings about that, writing "For not without reason have the ancients handed it down as Paul's. But who wrote the epistle, in truth, God knows" (Eccl. History 6.25.13-14). Other possibilities like Silas, Timothy, or Apollos have also been offered, yet the book remains anonymous. The same is not true of the gospels; they are always and confidently ascribed to these four authors and no other possibility is ever advanced. Further, when the second century produced a flurry of forged gospels, such as the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Peter, these were summarily rejected because they were forgeries. There does not exist any ancient list or writing offering as authoritative any accounts of Jesus's life other than Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This is strong evidence that the early church fathers were critical of claims that an apostle wrote a book without any good supporting evidence for it that ties it all the way back to the apostles themselves.What's More Reasonable?

Given all that we know about the gospels, the testimony of people like Papias who sought to establish their relation to the eyewitnesses, the internal testimony and claims that they were written by eyewitnesses, and the lack of other options, it is more reasonable to hold that the gospels were written by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John than to believe they are forgeries.References

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Who Wrote the Gospels – Evidence for John

John's Gospel: The External Evidence

John most probably wrote his gospel last, possibly even into the early 90's, though there's some debate about that. One would think that since the early church historian Papias was alive and collecting his sources at the time of the different gospels' authorship, this would be the easiest of the four to identify. Unfortunately, it isn't that cut and dried. The quotation from Papias isn't as clear as we would like.Eusebius, when he quotes Papias on John's gospel records that Paipas seems to list John the apostle, grouping him with the likes of Andrew, Peter, James, Philip, and Thomas. This group Papias labels "the elders." He then mentions "other disciples of the Lord' which seems to imply those who also heard Jesus's teachings. 1 However, Papias lists another John, whom he calls "John the Presbyter" as well. This John is also called "The Lord's disciple," but Eusebius thinks that this John is different from the apostle, and this use of the term disciple in this second instance may be more generic; it is a way of identifying a follower of Jesus's teachings and not one who sat under Jesus himself. Others disagree and say the phrase is to focus those disciples who were still alive and teaching in churches in Asia.2,3

That doesn't mean we have no testimony on authorship of the fourth gospel from the early church fathers. The claim that Apostle John was the author is made by Irenaeus, who tied it to the epistles of John and the book of Revelation.4 The second century church father Polycrates, writing about AD 190, stated that John "was both a witness and a teacher, who reclined upon the bosom of the Lord."5

John's Gospel: The Internal Evidence

While we cannot point with certainty to Papias, we can at least deduce from early on the author of the Gospel was someone named John. That's actually helpful, as the author of John's Gospel does include himself in the narrative, but never by name. He always refers to himself as "the disciple whom Jesus loved," such as in John 21:20 where Peter was questioning his fate. He then makes a bold claim: "This is the disciple who is bearing witness about these things, and who has written these things, and we know that his testimony is true" (John 21:24). Here, we have the author claiming to be an eyewitness of the events he has written about. Knowing that the Beloved Disciple was present at the Last Supper (John 13:22) and leaning on Jesus's breast, it narrows this author down to one of the original twelve apostles. Given that Jesus charges him with the care of his Mother, Mary (John 20:26-27), this must've been not simply any disciple but one who was deeply intimate with Jesus.Yet, there is more evidence. Another claim to being an eyewitness is found at the beginning of the Gospel. In John 1:14, the author says, "The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory." That phrase of "his glory" is key. Jesus only revealed his glory one time, and that as on the Mount of Transfiguration. While that event is not recorded in John's gospel, it is captures in the other three, who are in agreement that Jesus took only Peter, James and John with him. It was big enough to make an impression on both Peter and John, given that Peter points to it in claiming his eyewitness credentials: For we did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty" (2 Peter 1:16).

When we look at John's three epistles, we can see that John uses the term "the elder" for himself (2 John 1:1, 3 John 1:1). The epistle writer also claims to be an eyewitness in 1 John 1:1-3: "That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life the life was made manifest, and we have seen it, and testify to it and proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and was made manifest to us that which we have seen and heard we proclaim also to you." Further, the style of the three epistles and the fourth Gospel are so close that it is clearly evident they were all written by the same person.

For John's Gospel we now know that:

- The author was an eyewitness of the events he recorded

- He was intimately acquainted with Jesus

- He was an elder in the church, providing instruction through much of the first century

- He wrote the three epistles that are also identified with the apostle John

- He claimed to not only see Jesus, but to see him "in his glory" which points to the Transfiguration

- Jesus's took only three of his closest disciples with him to see his transfiguration

- There is second century tradition that points to john the Apostle as being the author of the fourth gospel.

References

2. Bauckham, Richard. Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub., 2006. Print. 17.

3. Blomberg, Craig. The Historical Reliability of the Gospels. Second ed. Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity, 2007. Print. 27.

4. Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 5.8.4-5

5. Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 5.24.2

Monday, February 16, 2015

Who Wrote the Gospels - Evidence for Luke

The place to start when investigating the gospel attributed to Luke is actually the book of Acts. We begin here because the author tells us that Luke and Acts are a two-volume set, written by the same person to the same recipient. The book of Acts begins, "In the first book, O Theophilus, I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach, until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commands through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen" (Acts 1:1). This corresponds exactly to the opening of Luke's gospel where he writes:

Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught (Luke 1:1-4).Theophilus is addressed as the recipient in both accounts and the author claims to have direct access to eyewitnesses, thus scholars are agreed that the author of Luke is also the author of Acts.

The Early Authorship of Acts

The book of Acts records the actions of the early church and Paul's missionary journeys. Yet, the book stops rather abruptly at Paul's house arrest, yet before his trial in Rome. We know from Clement's writings (about AD 95) that Paul was released from Rome and visited "the extremity of the West."1 This is most likely Spain, as Paul himself said he planned to visit there in Romans 15:24. So, why would the author of Acts leave out such a victory as Paul getting exonerated and released at his trial in Rome? The only reasonable explanation is the book of Acts was completed before Paul was freed. This means that the book of acts was written around AD 62, placing the author in direct contact with most of the apostles. This still doesn't point to Luke as the author, but it makes the author at least a contemporary of Luke's.Luke Includes Himself in Acts

The biggest clincher in who authored Luke and Acts is the section beginning in Acts 16:10, where the author begins to include himself in the narrative. Up to this point Paul and Silas are referred to in the third person plural "they." Yet, at Troas, the pronoun switched to "we". When Paul and Silas were thrown in prison it switches back to "they" seemingly indicating that the author was not jailed with them. Yet, in Acts 20, when Paul and Silas come back to Troas, the "we" returns. Thus, the author traveled with Paul for some of his missionary journeys. Paul himself tells us that Luke was accompanying him, mentioning Luke by name in his letters (Col. 4:14, 2 Tim. 4:11, and Phil. 1:24). Irenaeus in the second century tell us that "Luke, the follower of Paul, set down in a book the Gospel preached by him," and in the earliest surviving writing after the apostolic writings (the Muratorian fragment, dated about AD 170) it states "The third book of the Gospel is that according to Luke. Luke, the well-known physician, after the ascension of Christ, when Paul had taken with him as one zealous for the law, composed it in his own name, according to the [general belief]." 2Given all the above, we know that the author of the Gospel of Luke:

- Also wrote the book of Acts

- Lived during the times of the events recorded in the Book of Acts

- Accompanied Paul on some portion of his missionary journeys

- Would have direct access to the apostles to interview them

- Is intimate enough with Paul to be mentioned by him in his later years

- Is claimed to be Luke by some of the earliest traditions.

References

2 Metzger, Bruce M. "The Muratorian Fragment." Early Christian Writings. 1965. 15 Feb. 2015 http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/muratorian-metzger.html.

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Hidden Ways the Gospels Prove Reliable (video)

Can we trust the Gospels? Why should people place their trust in documents written so long ago that don't even agree with each other? In this video given at last year's Speaking the Truth in Love Conference, Lenny investigates two little-known pieces of evidence that demonstrate why the Gospels are reliable history.

Friday, February 13, 2015

Who Wrote the Gospels – Testimony from the Church Fathers

For example, take the authors of the Gospel accounts. We know that the four Gospels were not signed by Matthew, Mark, Luke or John. This is not uncommon, as there were other popular biographies that were also anonymous when written. However, there are good reasons to hold that the Gospels were written by these four men. Let me begin by reviewing the historical tradition linking the four to the Gospel accounts.

The Testimony of Clement

While Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John did not sign their names to their Gospels, the church recognized them as the authors very early in its history. Eusebius, writing at the end of the third century specifically credits the four Gospels to those four writers. Of course, writing about authorship some 200 years after the Gospels were composed may lead people to wonder just how reliable that is. But Eusebius didn't make the connection himself. He quoted from earlier works such as Clement of Alexandria.Clement of Alexandria lived 100 years before Eusebius and held that Mark wrote his Gospel, taken from the teaching of Peter. He also notes that this Mark is the one Peter mentions in 1 Peter 5:15 (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.15.1-2).1 He later states that Mark's writing of the Gospel happened while Peter was still alive (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 6.16.6).2

The Testimony of Papias

While Clement's writings bring us to within a century of the Gospels' composition, Eusebius quotes and even earlier source, the writer Papias. Richard Bauckham notes that Papias' writings, while composed probably around 110AD are reflections from his earlier investigations as he collected oral reports from disciples who sat under either the apostles' direct disciples or the apostles themselves. Bauckham notes "the period of which he is speaking must be around 80CE."3 According to Craig Blomberg, Papias states Mark, who served as Peter's interpreter, "wrote accurately all that he remembered, not indeed, in order, of the things said and done by the Lord."4Similarly, we have early support for the other authors as well. Blomberg notes that Papias tells us that Matthew wrote his gospel "alleging that he originally wrote the ‘sayings' of Jesus in the Hebrew dialect."5 Irenaeus, who lived just after Papias confirms that Matthew wrote his gospel and did so early: "Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church" (Against Heresies 3.1.1). Clement of Alexandria, in the same Eusebius passage where he confirms Mark authorship also confirms Luke and John's authorship of their gospels.

Next time, I will look at some additional reasons why he hold these four men as the proper authors of the Gospel accounts. For now, we can know that there is a strong chain of testimony linking these men to the Gospel accounts.

References

2. Christian Classics Ethereal Library, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201.iii.xi.xiv.html.

3. Bauckham, Richard. Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub., 2006. Print. 14.

4. Blomberg, Craig. The Historical Reliability of the Gospels. Second ed. Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity, 2007. Print. 25.

5. Blomberg, 26.

Monday, February 09, 2015

How to Quickly Debunk the Horus-Jesus Myth

I should have known better. While the name of our shared friend lent some credence to the tale, it's obvious that the whole this is too sensationalistic and improbable to be true. It's what used to be called a tall tale, a yarn, a cock-and-bull story. Yet, even though I found it fascinating, the legend didn't spread much beyond our conversation. However, now that social media has been implanted into our circulatory systems, we're much more apt to spread such fertilizer in our interactions with others.

The Horus-Jesus Myth: What's the Connection?

Such is the case with the "Jesus is a copy of pagan myths" trope that seems to be gathering steam in many atheist circles. Some of this has to do with the popularity of the YouTube video Zeitgeist, where the first third of the video tries to compare Jesus and several demi-gods worshipped prior to Jesus's birth. Near the beginning, the narrator makes this claim:Broadly speaking, the story of Horus is as follows: Horus was born on December 25th of the virgin Isis-Meri. His birth was accompanied by a star in the east, which in turn, three kings followed to locate and adorn the new-born savior. At the age of 12, he was a prodigal child teacher, and at the age of 30 he was baptized by a figure known as Anup and thus began his ministry. Horus had 12 disciples he traveled about with, performing miracles such as healing the sick and walking on water. Horus was known by many gestural names such as The Truth, The Light, God's Annointed Son, The Good Shepherd, The Lamb of God, and many others. After being betrayed by Typhon, Horus was crucified, buried for 3 days, and thus, resurrected.Richard Carrier also believes that resurrection stories were "wildly popular among the pagans" and begat a something akin to the standard trope, with the Gospels simply following in this tradition:

These attributes of Horus, whether original or not, seem to permeate in many cultures of the world, for many other gods are found to have the same general mythological structure.1

Among pagans, genuine sons of god who had to be murdered, buried, and then miraculously resurrected from the dead in order to judge and rule from heaven on high as our divine saviors were actually a common fad of the time, not a shocking novelty at all. Osirus and Romulus were widely worshipped to the tune of such sacred stories demonstrably before the rise of Christianity, and similar stories surrounded other dying-and-rising gods long before such as Zalmoxis, Adonis, and Inanna.2

The Horus-Jesus Myth: Be Critical

Just like the stolen kidney story, the Horus-Jesus connection myth has much of what makes an urban legend appealing: a moral tale that shows how one's gullibility can result in one being taken in with serious consequences, the authoritative yet undefined source, a set of facts that on the surface are seemingly plausible, and the ability to shock others with a sensational revelation. Yet, just like the stolen kidney story, all you need to do is to think a bit and the paper-thin claims of Jesus's stolen resurrection will quickly melt away. Here are five points to consider:1) Look for Loaded Language

Notice in the Zeitgeist story, all the terms used are ones taken from Christianity. Horus is called a "messiah" and was "baptized." He had "disciples" and a "ministry." All of these terms bias the listener because they are Jewish or Christian concepts. The Egyptians would never use these words to refer to their religious rites. The word messiah had a very specific meaning to the Jews, including being a descendant of David. It wasn't any political figure. Christianity teaches that believers are baptized only once, not simply a pre-religious washing ceremony. By mislabeling other deities with Christian terms, the listener is deluded into believing the similarities are closer than they really are.

2) Ask "Can I read the source of these myths?"

The single easiest way to debunk these supposed parallel accounts of Jesus and Horus are to simply ask for the source text of the myths themselves. Just as the stolen kidney tale can't be verified since it comes from "a friend of a friend," so you'll find that the ancient tales that supposedly parallels the life of Jesus are an extended form of hearsay. In fact, all these claims are usually committing the same sin many atheists claim the Gospels commit: they are more like a game of telephone than real texts.

Interestingly, if anyone actually bothers to look up the source texts, a very different picture arises. For Horus, there's no mention at all of twelve disciples, three king visitations, and death by crucifixion and the three day entombment. In fact, Horus was stung by a scorpion and a magic incantation by the god of wisdom, Thoth, purges the venom from his body. This all happens while Horus was a young child, well before his adulthood and battle for the throne. It's nothing like Jesus's resurrection at all.3

3) Ask "What do you mean by "resurrection?"

There's a significant difference between Jesus's resurrection and what you read in the ancient myths. Osirus, according to a late tradition recorded in the first century AD by the Roman Plutarch, was cut into fourteen pieces by his nemesis Typhon and they were scattered all along the Nile. Osirus's wife Isis was able to gather thirteen of those to reassemble her husband. The tale tells us that unfortunately Osirus's sexual organ was eaten by fish and so Isis assembled another out of gold in order for Osirus to impregnate her with Horus. Osirus, since he will never be a complete being again, now resides as the god of the underworld.4

4) Ask "What do you mean by virgin birth?"

Certainly, given the events above, calling Horus's conception a virgin birth strains the idea to its breaking point. Other fables, such as Zeus impregnating Semele with Dionysus. He had physical relations with her even though she couldn't see him. Zeus took Dionysus as a fetus and sewed him into his thigh and from there Dionysus was born. To say the virgin birth stories should be considered comparable is itself laughable.

5) Ask "Just which calendar were they using in ancient Egypt?"

Lastly, the claims of December 25th are completely erroneous. Many myths don't specify any date at all for the birth of the deities (again, read the originals!) For Horus, Plutarch tells us he was born "about the time of the winter solstice… imperfect and premature."5 Beside the fact that Plutarch mixed many Greek ideas with the Egyptian myths, it is a huge stretch to assume an exact date for Horus's birth. Taking Plutarch's account, the term "about the time of the winter solstice" can be a swing of weeks in either direction. But if the Egyptians wanted to be more precise and attach Horus with the solstice, then his birthday would be the 21/22 of December in the modern calendar, not the 25th. As I've explained before, Jesus's actual birth is not known, and celebrating Christmas on December 25 has nothing to do with the winter solstice whatsoever.

There are other ideas you should have at the ready as well. For more suggestions, see here and here. But it should be evident by now that the supposed evidence of Christianity's plagiarism of earlier myths is itself based on myths and contrivances. Those that offer such views attempt to paint a picture that doesn't exist. Don't let these organ thieves steal your brain. Challenge them to think.

References

2. Carrier, Richard. "Christianity's Success Was Not Incredible". The End of Christianity, John Loftus, Ed. (New York: Prometheus Books, 2011). 59.

3. Budge, E. A Wallis. " The Legend of the Death of Horus - II.--The Narrative of Isis " Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian Texts, Edited with Translations. London: Kegan Paul, Trench and Trübner, 1912. 170-196. Print. Online text available at http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/leg/leg28.htm

4. Budge "The History of Isis and Osiris -Section XVIII." 224-226. Web. http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/leg/leg46.htm

5. Plutarch. Isis and Osiris. Loeb Classical Library ed. Vol. V. N.p.: Loeb, 1936. Bill Thayer's Web Site. University of Chicago, 9 Oct. 2012. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Isis_and_Osiris*/D.html.

Friday, January 30, 2015

Why You Can Be Confident We Have the Original Bible Texts

But Eichenwald doesn't argue that multiple translations are the only problem in discovering the original text. He also mentions the fact that we don't have the original writings of the New Testament, but "hand-copied copies of copies of copies of copies, and on and on, hundreds of times."1 There is a bit of truth to this claim. If the manuscripts from which we are translating the New Testament are themselves corrupt or wrong, then it really doesn't matter how well we have translated the text. We're simply translating an error. Let's examine this critique and see if it holds up.

First, it is true that we don't have the originals, or the first generation copies, or even the second generation. While we don't know just how many times the text was copied prior to the earliest copes we do have (called manuscripts), it is safe to say they are for the most part dozens of times removed from the originals. What makes things seem worse is the earliest pieces we do have are not large portions of text, but small fragments. For example, the earliest gospel portion is the John Rylands fragment (P52) that only contains part of John 18:31-33 on one side and John 18:37-38 on the other. The more complete manuscripts are from hundreds of years later.

Doesn't the fact that we are separated by hundreds of years from the originals to the copies we have cause concern? Actually, not at all. New Testament scholars—both Christians and skeptics—have the greatest confidence that we know just what the original authors wrote. How can this be? I can explain with an example: tracing my family's recipe for spaghetti sauce.

Nonna's Family Sauce

My great grandmother came to the United States from

Sicily in 1921. With her, she brought a recipe for spaghetti sauce that her

mother had cooked. She in turn taught it to her three daughters, of which my

grandmother was one. My grandmother passed that along to her four children,

including my mother. She taught it to my wife and my siblings and my wife taught

it to my daughter-in-law. The other daughters passed the recipe onto their

children who passed it to theirs as well.

My great grandmother came to the United States from

Sicily in 1921. With her, she brought a recipe for spaghetti sauce that her

mother had cooked. She in turn taught it to her three daughters, of which my

grandmother was one. My grandmother passed that along to her four children,

including my mother. She taught it to my wife and my siblings and my wife taught

it to my daughter-in-law. The other daughters passed the recipe onto their

children who passed it to theirs as well. Now, suppose the descendants of my Great grandmother all get together at the 200th reunion of her arrival and say, "we want to make the sauce, but we want to make sure that it is the exact sauce she would have tasted in Sicily as a little girl." Would such a feat be impossible? Not really. In order to find the original, all the families would write down their recipe as they now fix it. There would be more than a hundred copies of the recipe, and there would no doubt be variations in the ingredients, amounts, and preparation. However, because we have such a large collection, we can begin to compare them one to another.

We may notice that all the recipes use crushed tomatoes except for 20 which say tomato sauce. We also not the crushed tomatoes show up nearly unanimously in the recipes supplied by the older generations. It is a strong bet that crushed tomatoes is right. Secondly, we notice that one group of recipes call to use twice as much garlic in the sauce. But all of these recipes come from the family of one uncle who liked the strong taste of garlic. Another group tell us to add sugar, but that cousin was known to have a sweet tooth. Some are missing ingredients, others have the preparation steps reversed, and a few add meat. However, because we have so many copies, we can reasonably rebuild the original recipe. Those copies coming from the older generations are less likely to deviate from the original since they have gone through fewer iterations. Overall, though, the receipt they come up with is probably the one my great grandmother was served as a little girl.

Thousands and Thousands of Copies

Those who reconstruct the text of the New Testament do basically the same thing on a larger scale. They have many thousands of manuscript copies, partials, and portions from different places all over the ancient world. New Testament scholar Dr. Daniel Wallace places this in perspective when he writes:Altogether, we have at least 20,000 handwritten manuscripts in Greek, Latin, Syriac, Coptic and other ancient languages that help us to determine the wording of the original. Almost 6000 of these manuscripts are in Greek alone. And we have more than one million quotations of the New Testament by church fathers. There is absolutely nothing in the Greco-Roman world that comes even remotely close to this wealth of data.2This is why scholars today have a 99% confidence level that the text of the New Testament we have is what the original authors wrote.

I've only scratched the surface of Eichenwald's article; there are many more claims about the Bible he makes that fail to take modern scholarship into account. These two points, though, should give you confidence that his claims about no one today "has ever read the Bible"3 are unjustified. We do have the books as the New Testament authors wrote them. I would bet a plate of pasta on it.

References

2. Daniel B. Wallace. "Predictable Christmas Fare: Newsweek's Tirade against the Bible." Daniel B Wallace. The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts, 28 Dec. 2014. Web. 30 Jan. 2015. http://danielbwallace.com/2014/12/28/predictable-christmas-fare-newsweeks-tirade-against-the-bible/.

3.Eichenwald, 2014.

Monday, January 26, 2015

Is the Bible Reliable Since Its Been Translated So Many Times?

The reason we attempted such silliness is to try and intentionally confuse the translating robot. We knew that churning out a translation of a translation would force mistakes to be multiplied, a realization that takes no scholarship at all. Yet, this is the way many people assume the scholars responsible for our modern bibles have worked. Yesterday, a gentleman at my church said he had been in a conversation with a Muslim who said, "Your Bible has been translated so many times challenged by a Muslim on the validity of the Bible as it compared to the Qur'an." This isn't an uncommon claim and many atheists and non-believers have tried to make the same point.

Take the Newsweek cover story published just two days before Christmas entitled "The Bible: So Misunderstood It's a Sin." The article, which seems to take as its goal the undermining of biblical authority, is rife with inaccurate assumptions and misunderstandings about how biblical scholarship works. Interestingly, its very first criticism is at the problem of multiple translations. Author Kurt Eichenwald, under the heading "Playing Telephone with the Word of God," writes:

No television preacher has ever read the Bible. Neither has any evangelical politician. Neither has the pope. Neither have I. And neither have you. At best, we've all read a bad translation—a translation of translations of translations of hand-copied copies of copies of copies of copies, and on and on, hundreds of times.1That's the thinking that many people have. yet this perception is so incredibly wrong it takes my breath away. But Christians seem to not know how to respond to such accusations, as the question posed to the man at church shows.

Counting Up the Number of Translations to You

The first thing I emphasize when tackling the objection that we are somehow insulated from the real meaning of the Bible because of so many translation is to simply ask, "how many times do you think the Bible version you have has been translated from its original languages?" People are feign to guess, imagining perhaps ten, dozens, or more. The reality is that every modern Bible translation has been translated exactly once from the original Greek and Hebrew. Once. That's all. There is no "translation of translations of translations." Biblical scholars work directly from the Hebrew and Greek texts to create the English versions we have today. Eichenwald could have seen that if he had bothered to look at the prefaces to any Bible. Here's what the Translation Committee for Crossway, which publishes the English Standard Version states:"each word and phrase in the ESV has been carefully weighed against the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, to ensure the fullest accuracy and clarity and to avoid under-translating or overlooking any nuance of the original text."2Here's what the Lockman Foundation, who created the New American Standard Bible says:

The New American Standard Bible has been produced with the conviction that the words of Scripture, as originally penned in the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, were inspired by God… At NO point did the translators attempt to interpret Scripture through translation. Instead, the NASB translation team adhered to the principles of literal translation. This is the most exacting and demanding method of translation, requiring a word-for-word translation that is both accurate and readable. This method follows the word and sentence patterns of the original authors in order to enable the reader to study Scripture in its most literal format and to experience the individual personalities of those who penned the original manuscripts.3Here's what the NIV translation committee explained:

In 1965, a cross-denominational gathering of evangelical scholars met near Chicago and agreed to start work on the New International Version. Instead of just updating an existing translation like the KJV, they chose to start from scratch, using the very best manuscripts available in the original Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic of the Bible.4And just to show that this translation approach is not something that only began recently, here's what the translators wrote in the preface to the original 1611 King James Version:

That out of the Originall sacred tongues, together with comparing of the labours, both in our owne and other forreigne Languages, of many worthy men who went before us, there should be one more exact Translation of the holy Scriptures into the English tongue; your MAJESTIE did never desist, to urge and to excite those to whom it was commended, that the worke might be hastened, and that the businesse might be expedited in so decent a maner, as a matter of such importance might justly require (emphasis added).5Note that the translators state that they look at the originals and then look at other translations (the "many worthy men who went before us," such as Tyndale) to be better informed on their own word choice. Consulting existing translations is actually a benefit, as it adds more counselors to the translation efforts, not fewer. Yet, each and every translation begins and is compared against the original languages to ensure accuracy and compatibility. Your Bible, no matter which translation you choose, has been translated only one time, and straight from the original languages to English.

References

2. The Translation Oversight Committee. "Preface to the English Standard Version." About ESVBibleorg. Crossway, n.d. Web. 26 Jan. 2015. http://about.esvbible.org/about/preface/.

3. The Lockman Foundation. "Overview of the New American Standard Bible." The Lockman Foundation. The Lockman Foundation, n.d. Web. 26 Jan. 2015. http://www.lockman.org/nasb/index.php.

4. "The NIV Story." Biblica. Biblica, 13 Dec. 2013. Web. 26 Jan. 2015. http://www.biblica.com/en-us/the-niv-bible/niv-story/.

5."King James Version Original Preface." DailyBible.com. BibleNetUSA, 2006. Web. 26 Jan. 2015. http://www.kjvbibles.com/kjpreface.htm.

© 1999 – 2014 Come Reason Ministries. All rights reserved.