One particularly striking section dealt with a character named Shame. Christian's friend Faithful recounts to him Shame's accusations against believers. Specifically, Shame claims the religious are basically weak-minded individuals, not living in the real world. He goes on to point out how successful and intelligent people don't believe in such things and how believing in Christianity forces one to ignore the scientific advancements and knowledge of the day. "He moreover objected to the base and low estate and condition of those who were chiefly the pilgrims of the times in which they lived; also in their want of understanding in the natural sciences." 1 So, Shame accuses the Christians of being willfully ignorant. Ignoring what he holds to be the true knowledge of science, Shame charges Christian with substituting the crutch of religion to salve his wounds.

Our Popular Conception of Science

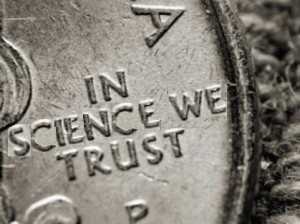

Today, we are even more apt to hear such objections to believing the biblical message. This is in large part due to the over-emphasized view science is given in our modern culture. Science is understood in today's world to be the only reliable source of truth. One has only to look at the advertisements we use to sell products to see how much we esteem the concept of scientific veracity. If you really want to make your case for the potency of a product, just have your spokesman wear a white lab coat, begin his name with Dr., or explain how "tests have shown" the item to be more effective. If science has shown something to be true, then it must be true. And if there is a conflict between beliefs and what science has shown, then most people will assume that it is our beliefs that are in error, not science.These assumptions are unfortunate, but not altogether unsurprising. As I've said before, science has helped humanity in incredible ways. Our lifespan have been extended by decades, we can modify our environment if we're too hot or too cold, and technology has made our daily chores easier. Our learning has also increased exponentially; we better understand the way the world works, we can predict certain phenomena and we've even visited the moon! So with all science has proven it can do, how could it not be real way to know truth?

Scientism's Claim to Truth

There are two problems we run into when discussing science and the way we know things to be true. The more egregious error is the one the easier to identify and argue against. That is the belief that only things that are scientifically verifiable are truly knowable and everything else is opinion and conjecture. This view is known a Scientism, and has had proponents such as Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking and the late evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould. Noted skeptic Michael Shermer defined Scientism as "a scientific worldview that encompasses natural explanations for all phenomena, eschews supernatural or paranormal speculations, and embraces empiricism and reason as the twin pillars of a philosophy of life appropriate for an age of science." 2The proponents of Scientism hold that "only things that are scientifically verifiable are truly knowable", is a true and knowable statement. However, that statement is itself unverifiable scientifically. One cannot construct a hypothesis to test for the statement's veracity. There's no way to go into a laboratory and run this idea through a battery of tests to see whether it can be falsified. Scientism, by setting a standard that cannot itself meets, undercuts its own existence. It becomes what we call a self-refuting statement. Because it does so, Scientism should rightfully be rejected as illogical.

Who Chooses the Standard of Comparison?

The main problem with our popular view of science, though, is more subtle and it therefore takes more care to identify. Because science has taken such a high role in our society, statements that are couched in a scientific approach are thought to hold more weight than other types of assertions. However, many who are purporting to advance a scientific view are really making philosophic statements - and they're making a lot of assumptions along the way.A good example of this is one that Christian philosopher Francis J. Beckwith related to me at dinner one evening. He told of how he had become engaged in a discussion on origins through an Internet bulletin board whose members were primarily biologists and other scientists. One member was asserting the fact of evolution by noting how science has shown human DNA and chimpanzee DNA to be 98% identical. The biologist then concluded that this proves humans and chimps share an evolutionary ancestor.

Dr. Beckwith countered this claim by asking a simple question: Why do you choose genetics be your basis of comparison? It seems an arbitrary choice. Why not any other field of science, say quantum mechanics? Dr. Beckwith went on to explain that if you examine humans and chimpanzees at the quantum level, why then we're 100% identical! Our atoms move and act in exactly the same way as the atoms of the chimp! Of course, human atoms and the atoms of the table where I'm writing this also act identically. How about if we examine each via physics? Again, we're identical: each species will remain in motion unless enacted upon by an outside force, for example.

The scientists had a very difficult time understanding Dr. Beckwith's point, but it was simply this: one cannot start with science to understand the world. Science relies on certain philosophical rules in order to work at all. What was happening is the biologist was making philosophical assumptions and then using science to try and support them. The assumption in the claim above is that all life can be reduced to its genetic make-up, and everything you need to know about any living thing can be deduced from its DNA. It's this assumption that's flawed. It doesn't follow that if humans share 98% of their DNA with chimps that evolution is therefore a fact. But the scientists today aren't trained in logic or philosophy, so they have a lot of difficulty understanding that they are making flawed philosophical arguments and packing them in scientific facts.

References:

1. Bunyan, John The Pilgrim's Progress

Baker Book house, Grand Rapids, MI 1984 p.89

2. Shermer, Michael "The Shamans of Scientism" Scientific American June 2002

Accessed online at: http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=000AA74F-FF5F-1CDB-B4A8809EC588EEDF

Baker Book house, Grand Rapids, MI 1984 p.89

2. Shermer, Michael "The Shamans of Scientism" Scientific American June 2002

Accessed online at: http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=000AA74F-FF5F-1CDB-B4A8809EC588EEDF

.JPG)